|  |

|

American Barn Owl - Tyto alba Sole representative of TYTONIDAE in NC | Search Common: Search Scientific: |

|

|

||||||

| General Comments |

The American Barn Owl is a completely nocturnal feeder; thus, its presence in a given area can be difficult to determine, and censuses of population numbers are not easy to obtain (i.e., they are seldom encountered on Breeding Bird Surveys). Yet, birds will nest in silos, barns, abandoned sheds, and hollows of trees, mostly in farmland. They even utilize man-made nest boxes, where placed on barns and other structures, in open country. The species also breeds along the coast, nesting in places such as duck blinds. This is our most "non-forest" owl, though birds roost in cedars or dense stands of pines, at least near the coast in the cooler months. The American Barn Owl has undergone a considerable decline as a breeding and wintering species in the state and over nearly all of the East, as its favored habitat of farmlands and other open fields have been decimated by development and abandonment, and old farm buildings decay or are destroyed. Even in coastal areas, where the species forages in marshes, the species has clearly declined, at all seasons, for reasons that are not well understood (though Great Horned Owl predation has been suggested as one cause), as brackish and fresh marshes near the coast do not seem to have been overly impacted. In the past few decades, it must now be called a rare bird in the state, and many relatively new birders have yet to see or hear one in the state. In October 2017, the species was added to the State protected list, as Special Concern.

NOTE: In 2024, the AOS (Formerly AOU) added the modifier "American" to the common name, to distinguish the name from two others, named as Western Barn Owl and Eastern Barn Owl, neither of which occurs in North America. | |||||

| Breeding Status | Breeder | |||||

| NC BRC List | Definitive | |||||

| State Status | SC | |||||

| U.S. Status | ||||||

| State Rank | S2S3B,S3N | |||||

| Global Rank | G5 | |||||

| Coastal Plain | Permanent resident, with migratory movements; noticeably declining (since around 1970). Along the coast and in the Tidewater zone, mostly rare to uncommon in the cooler months, and seemingly now rare as a breeder, though such data are sparse. Farther inland, very rare to rare (at least rarely reported) at all seasons, though possibly occurs in all counties. Peak counts (not of nesting pairs plus young): 4, Lake Mattamuskeet, 6 Nov 1954. | |||||

| Piedmont | Permanent resident, probably with migratory movements; certainly declining. Rare to locally uncommon in the southwestern portion of the province, probably most numerous in Lincoln, Gaston, and Cleveland. Elsewhere, very rare to rare across the province, probably occurring in all counties, but not well known in many areas. Peak counts: ? | |||||

| Mountains | Permanent resident, likely with migratory movements; presumed declining. Rare in valleys in the southern counties (below 2,500 feet), essentially in Buncombe, Henderson, and Transylvania; casual to very rare elsewhere and at higher elevations. Quite notable were two broods of 5 owlets each at a farm in Piney Creek (Alleghany) in summer 2014. Peak counts: one pair. | |||||

| Finding Tips |

American Barn Owls must be searched for intentionally. You are not likely to stumble upon them in general birding. There are several possible methods for finding them. First, you can wait around coastal marshes, or other extensive grassy areas, around dusk, and hope to see them flying around. They can sometimes be seen at night flying over such areas, with the assistance of car headlights. Barn Owls used to be fairly common along the Outer Banks, especially at Bodie Island; one had a moderate chance of seeing one in your headlights as you drove the Banks or drove the length of the Lake Mattamuskeet causeway. Now, the species is much less common, but occasional sightings are still made.

If a visual appearance by the owls is not made, you can occasionally attract one by squeaking on the back of your hand, by loudly "shiss-ing", or by playing taped calls. Of course, a calm night is best for these techniques. A third technique is quite labor intensive and usually unsuccessful. Poke you head into dense cedars or pines along barrier islands. Barn Owls used to be seen regularly in fall and winter in the pines along the road to Bodie Island visitor center, but the pines have grown so large that they no longer provide cover from pestering crows. A fourth technique is to poke into abandoned barns, tobacco sheds, and other old buildings on farms. You might be able to flush an owl.

* to ** | |||||

| Attribution | LeGrand[2025-02-03], LeGrand[2024-07-19], LeGrand[2023-03-21] | |||||

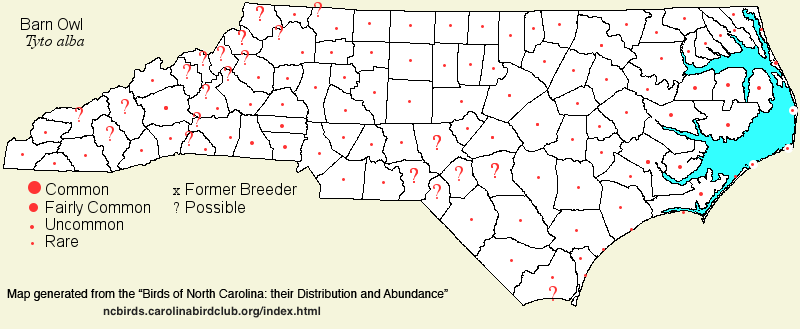

| NC Map Map depicts all counties with a report (transient or resident) for the species. | Click on county for list of all known species. |

| NC Breeding Season Map Map depicts assumed breeding season abundance for the species. |  |